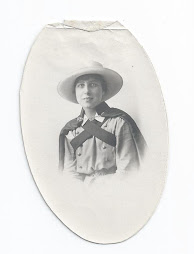

In several past blogs, I have been reconstructing the life of Carola Douglas through research and contributions by family members. However, family historian Anne Douglas has gone even farther. She has done extensive research on Carola and has come up with information that really casts light on this adventurous woman. With her kind permission, I am providing you with an excerpt of her account, along with photographs from her husband's family collection. As Anne writes:

"Carola Josephine Douglas was born in Costa Rica in 1874. One of four children born to Captain Andrew Trew Douglas and his wife Juanita...Andrew was 12 years old when he emigrated from Co. Armagh, in Ireland, with his parents and eight siblings in 1844.

He learned to be an engineer and a sea captain on the Great Lakes of his new land. He then left Canada to sail the oceans of South America, and led a very adventurous life. It was in Panama that he met his wife to be, Juanita Lanus(Lasas), a lady of Spanish descent.

Andrew and Juanita’s first two children, John Taylor and Elise were born in Panama in1868 and 1871.Then Andrew became very successful using his engineering skills, consulting on many ventures in South America including the Panama railroad and the French attempt to build the Panama Canal. This eventually led the family to projects in Costa Rica, and it was here that Carola Josephine was born in 1874 and then another brother, Arthur, my husband’s grandfather in 1877. It has been said that the whole family were fluent in the Spanish and English language. [The couple also had two other children, John Taylor, Elise, and Arthur--Anne's husband's grandfather.]

In May 1884 Andrew, Juanita and their children travelled from Panama to New York...A few days after their arrival, Andrew became gravely ill and died. Within a couple of days Juanita also died leaving their children as orphans."

The Douglas children were taken in by family members in Toronto and Winnipeg. From there on, their early origins were forgotten (at least in census records) and they were listed as Canadian born and their ages were also often incorrectly recorded. According to Anne Douglas, "Carola’s nursing career began at the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia," and the young woman was a frequent traveller, living in New York, but visiting places as far afield as Bermuda, Yugoslavia, Panama, England and Scotland.

In 1915, "Carola’s trip to Australia was cut short, when she heard that war had broken out in Europe. She travelled to Canada, presumably to the home of her sister Elise, who lived in Winnipeg, Manitoba," writes Anne Douglas. "It was here that Carola then enlisted in the Canadian Army Medical Corps [Toronto Star Obituary

On the 18th of February, 1915 Carola arrived at Liverpool, England aboard the S.S. Zeeland. Her sailing companions were the brave men and women of the first contingent of the C.A.M.C. Netheravon House in Wiltshire was Carola’s first destination. This was a convalescent home for wounded Canadian troops, and it was here that Carola’s attestation papers were signed on March 4th 1915."

The rest of Carola's story you will find in previous blogs on this site. However, Anne Douglas's closing remarks should be shared: "Nursing Sister Carola Josephine Douglas, fulfilled her destiny, and is remembered forever for her love, and courage in the line of duty." Thanks Anne!

Note: Please look at the photograph "Canadian Nurses." It is from Carola Douglas' album, and Anne Douglas would love to be able to identify the women pictured. If you might have information, please email me at the contact information provided on my blog.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

New Resources on Women and WWI

Hello again. My research has been slowed this month by changes at Library and Archives Canada. Cutbacks, changes to how materials are ordered, have meant that I am still waiting for more archival material to arrive. However, several files are now on their way to me, so I should be able to provide you with some interesting profiles very soon. Until then, I've got a few books to recommend.

There are some really good books coming out at present not only on the women who served during the Great War, but the ways in which we can find out more about them.

Tracing Your Service Women Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians (Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2012) by Mary Ingham is a superb resource for anyone wanting to track down information about women in several different military services (and in various conflicts). A researcher specializing in nurses and women who served in the First World War, Ingham provides information about the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), Army Schoolmistresses, the Territorial Force Nursing Service, VADs, First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), military and naval masseuses, Royal Army Medical Corps, RAF women doctors, Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and many others.

Countless Canadian women, frustrated by the limited openings in our own Canadian services, went overseas to serve in these British organizations. Ingham provides practical help to researchers who want to track down these women. She also gives us an insight into what these women's lives were like on a day to day basis, as this short passage suggests: "Author Naomi Mitchison served as a nursing VAD at St. Thomas's (part of 5 LGH) in 1915. She was clumsy at first. Having had servants all her life, she didn't know how to squeeze a mop or that tea was made with boiling water. However hard they worked, emptying bed pans, polishing lockers, scrubbing floors, the VADs were scolded or ignored. Only one sister ever explained what was wrong with the patients. Eventually, VADs were allowed to take temperatures and wash patients. Once Naomi was allowed to sit down--unthinkable, normally--to mark bottles. Beds had to to be made with perfect hospital corners tightly tucked in, regardless of patient comfort."

Ingham makes it clear that being a service woman was not for the faint of heart. Speaking of nurses, she writes: "One month you could be working in clean, dry wards in a solid building with running water and a comfortable billet with nice food in a small town; a couple of months later, surrounded by utter devastation, miles from anywhere, stumbling through old dugouts and stray barbed wire; a few weeks after that, in pretty woods, then back among shell holes...As the war progressed landmines, tanks and flamethrowers brought other dreadful kinds of injury and terrible head or stomach wounds. QA Reserve Lily Petter knew which she dreaded most--she slept with her tin hat over her stomach, not her head."

A useful guide for researchers, Tracing Your Service Women Ancestors is a well-written, fascinating read for anyone interested in the exciting lives and contributions of the women who went to war.

A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland During the First world War, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012), edited by Sarah Glassford and Amy Shaw, is a welcome addition to the small but growing collection of books that explore the contributions of Canadian women during the First World War. Many of the topics explored in this volume have been overlooked or downplayed in previous histories of the war. For example, Margot Duley examines the knitters of Newfoundland. In a war in which men spent much of their time in damp, muddy trenches, there was an unending need for dry, clean socks. "Soldiers were incapacitated by frostbitten feet and by trench, or immersion foot," writes Duley. Women not only fulfilled the need for socks, but--as Duley relates--the Women's Patriotic Association (WPA) of Newfoundland did much more than that. Their roughly 250 branches and 15,000 members raised money, made mitts, scarves, mufflers and shirts, "as well as medical necessities such as pajamas, pillows, cases, bandages, and sphagnum moss(used to dress wounds)." Duley, an accomplished historian whose book Where Once Our Mothers Stood We Stand: Women's Suffrage in Newfoundland is also worth a read, makes it very clear that women's needlework was no trivial contribution to the war effort.

The other essays in this volume, cast light on topics as diverse as the contributions of girls, female university students, and Native women to the war effort, the response of women to the men who came back disabled, and the support (or lack thereof)provided for the wives of servicemen. Unheard of literary voices are also revealed. This is refreshing; the war is so often remembered only in the voices of the so-called "war poets" such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. However, many women wrote popular poetry and fiction during the war and these contributions are now almost entirely forgotten. In "Verses in the Darkness," writer Vicki Hallett describes the work of Newfoundland poet, Phebe Florence Miller. In poem after poem, the writer told "stories about men and women's experiences of the First World War." Many of these described women's responses to the conflict. In "The Knitting Marianna" (1916), Miller writes "She only said--'Oh heart so weary, The lonely years ahead! But living men are cold and dreary and one must knit,' she said."

Some of the most haunting features of A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service are the photographs used to illustrate the essays. In "Marks of Grief," historian Suzanne Evans, provides an image of war widow Madeline Jones in her mourning clothes, "a literal embodiment of grief." A particularly creepy image was the cover for the Sheet Music "I Want to Kiss Daddy Good Night," depicting a ghostly child creeping down the stairs while a spectral mother sits by the fire, with daddy somehow present in the smoke from the nearby fireplace. A postcard of a ghostly mother standing by her son's side among wartime ruins makes it clear that women were expected to support their sons' decisions to fight for King and country.

A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service provides a compelling taste of many different topics related to women and the Great War. The reader will long for more from these authors! Fortunately, the book has a useful bibliography and a description of the contributors. Highly recommended.

There are some really good books coming out at present not only on the women who served during the Great War, but the ways in which we can find out more about them.

Tracing Your Service Women Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians (Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2012) by Mary Ingham is a superb resource for anyone wanting to track down information about women in several different military services (and in various conflicts). A researcher specializing in nurses and women who served in the First World War, Ingham provides information about the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), Army Schoolmistresses, the Territorial Force Nursing Service, VADs, First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), military and naval masseuses, Royal Army Medical Corps, RAF women doctors, Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and many others.

Countless Canadian women, frustrated by the limited openings in our own Canadian services, went overseas to serve in these British organizations. Ingham provides practical help to researchers who want to track down these women. She also gives us an insight into what these women's lives were like on a day to day basis, as this short passage suggests: "Author Naomi Mitchison served as a nursing VAD at St. Thomas's (part of 5 LGH) in 1915. She was clumsy at first. Having had servants all her life, she didn't know how to squeeze a mop or that tea was made with boiling water. However hard they worked, emptying bed pans, polishing lockers, scrubbing floors, the VADs were scolded or ignored. Only one sister ever explained what was wrong with the patients. Eventually, VADs were allowed to take temperatures and wash patients. Once Naomi was allowed to sit down--unthinkable, normally--to mark bottles. Beds had to to be made with perfect hospital corners tightly tucked in, regardless of patient comfort."

Ingham makes it clear that being a service woman was not for the faint of heart. Speaking of nurses, she writes: "One month you could be working in clean, dry wards in a solid building with running water and a comfortable billet with nice food in a small town; a couple of months later, surrounded by utter devastation, miles from anywhere, stumbling through old dugouts and stray barbed wire; a few weeks after that, in pretty woods, then back among shell holes...As the war progressed landmines, tanks and flamethrowers brought other dreadful kinds of injury and terrible head or stomach wounds. QA Reserve Lily Petter knew which she dreaded most--she slept with her tin hat over her stomach, not her head."

A useful guide for researchers, Tracing Your Service Women Ancestors is a well-written, fascinating read for anyone interested in the exciting lives and contributions of the women who went to war.

A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland During the First world War, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012), edited by Sarah Glassford and Amy Shaw, is a welcome addition to the small but growing collection of books that explore the contributions of Canadian women during the First World War. Many of the topics explored in this volume have been overlooked or downplayed in previous histories of the war. For example, Margot Duley examines the knitters of Newfoundland. In a war in which men spent much of their time in damp, muddy trenches, there was an unending need for dry, clean socks. "Soldiers were incapacitated by frostbitten feet and by trench, or immersion foot," writes Duley. Women not only fulfilled the need for socks, but--as Duley relates--the Women's Patriotic Association (WPA) of Newfoundland did much more than that. Their roughly 250 branches and 15,000 members raised money, made mitts, scarves, mufflers and shirts, "as well as medical necessities such as pajamas, pillows, cases, bandages, and sphagnum moss(used to dress wounds)." Duley, an accomplished historian whose book Where Once Our Mothers Stood We Stand: Women's Suffrage in Newfoundland is also worth a read, makes it very clear that women's needlework was no trivial contribution to the war effort.

The other essays in this volume, cast light on topics as diverse as the contributions of girls, female university students, and Native women to the war effort, the response of women to the men who came back disabled, and the support (or lack thereof)provided for the wives of servicemen. Unheard of literary voices are also revealed. This is refreshing; the war is so often remembered only in the voices of the so-called "war poets" such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. However, many women wrote popular poetry and fiction during the war and these contributions are now almost entirely forgotten. In "Verses in the Darkness," writer Vicki Hallett describes the work of Newfoundland poet, Phebe Florence Miller. In poem after poem, the writer told "stories about men and women's experiences of the First World War." Many of these described women's responses to the conflict. In "The Knitting Marianna" (1916), Miller writes "She only said--'Oh heart so weary, The lonely years ahead! But living men are cold and dreary and one must knit,' she said."

Some of the most haunting features of A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service are the photographs used to illustrate the essays. In "Marks of Grief," historian Suzanne Evans, provides an image of war widow Madeline Jones in her mourning clothes, "a literal embodiment of grief." A particularly creepy image was the cover for the Sheet Music "I Want to Kiss Daddy Good Night," depicting a ghostly child creeping down the stairs while a spectral mother sits by the fire, with daddy somehow present in the smoke from the nearby fireplace. A postcard of a ghostly mother standing by her son's side among wartime ruins makes it clear that women were expected to support their sons' decisions to fight for King and country.

A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service provides a compelling taste of many different topics related to women and the Great War. The reader will long for more from these authors! Fortunately, the book has a useful bibliography and a description of the contributors. Highly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)